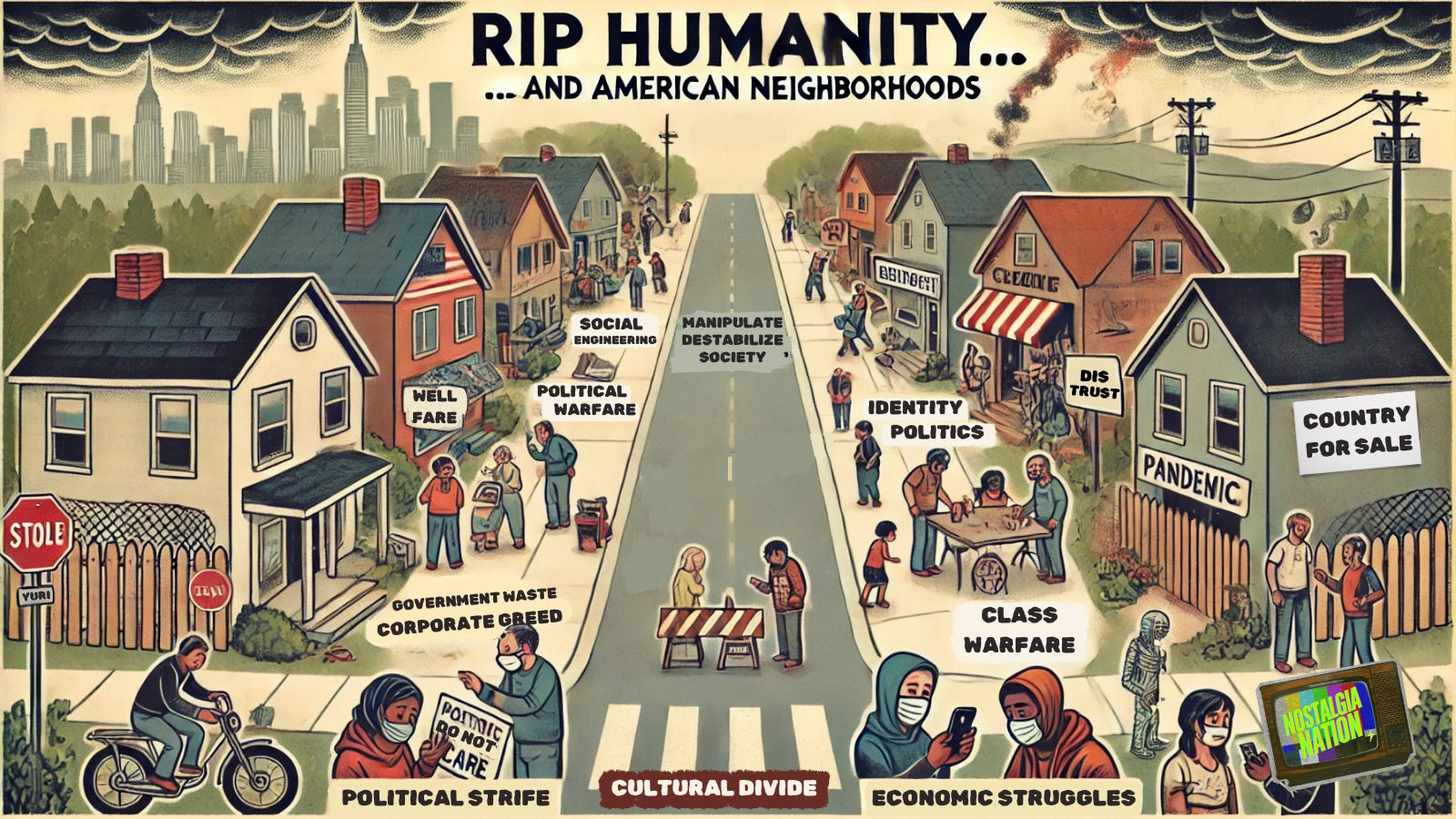

RIP Humanity... and American Neighborhoods

How we lost our sense of community and love for our neighbors

Remember when you actually knew the people next door?

Some of you still do, and I commend you for that. But for those of you that do, you know, deep down, something’s changed— not in a good way.

I’m writing this as a husband and father in my late forties, who happens to live in a beautiful San Diego suburb. This is quite the change from my youth, which was spent riding around the blighted neighborhoods of Detroit, MI. Things have certainly changed. Even then, when things were bleakest, I can recall just how much closer we were with our neighbors. We cared for the ones we knew really well, and still looked out for the ones that kept to themselves. I know they did for us.

As election day approaches, I generally steer clear of politics, but I can’t help commenting on culture. Having lived through over four decades of highs and lows, I’ve witnessed countless election cycles. Yet, none have left me as deeply concerned about the state of humanity as the recent decade. It saddens me to write this, but I believe what follows will resonate deeply with many of you, and that’s primarily because like me, you likely agree that people care less for one another far more today than any other time in recent history.

Let’s go back for a bit—

I’m a first generation immigrant and the oldest of five siblings. When we got to the United States I had already experienced life overseas (Greece, to be specific). I remember living through the destructive earthquake in Corinth/Athens in 1981, and camping out in the outskirts of the city with all of our neighbors as we waited out the tremors. Nearly everything was destroyed, including our small home. I recall the kindness of people experiencing that traumatic event together.

Later that year we arrived in Detroit, Michigan, where I began assimilating quickly, mainly because my parents were culture shocked. I could tell, even at a young age, that my parents were not going to transition easily. It was my birthday when we landed in the United States. I was exactly five years old, but I knew I would need to grow up quickly.

Detroit was a monster. Every day was a struggle. There were times we had one meal only. Somehow, my parents registered me in school. I think family members and The Red Cross helped, because my parents had no clue what to do. They bought cat food thinking it was tuna, and marshmallows thinking they were cotton swabs.

I got into scuffles almost every other day. I was behind, still learning the language, and I wasn’t white or black, so both picked on me. Every now and then, a neighbor would come out of their home and they would stop something from getting worse when they heard a group of kids yelling at each other. It was like they knew. This happened more than you think off 7-Mile Road and State Fair. By the time I was ten, I’d gotten into so many street fights, I’d gotten a reputation for not backing down, so the fighting tapered off ever so slightly. Academics? Forget about it. I learned most of what I knew from street life and television.

The neighborhoods near the schools were an interesting place. Eventually, when you got big enough, the older kids that loitered around schools and the State Fair area didn’t care about your age. If you looked older, you became a target.

One day, the snow was so heavy that my mother practically had to force my father to drive me to school– which, back then, had to be really bad, because you were expected to be in school even if there was three feet of snow– we happened to come across a beat up Lincoln Continental that was stopped on the road. The driver, a burly black dude, probably in his late thirties, was shoveling snow from the front of the Lincoln, which had apparently stopped him from being able to drive any further.