The Origin Story of Polly Pocket - The Tiny Titan of Gen X Imagination

And a special letter from the creator's daughter, Kate Wiggs

Sometimes my inbox delivers something that stops me cold between caffeine hits and nostalgia scrolls. A few weeks ago, I got a message from kate wiggs, daughter of the late Chris Wiggs, the man who invented Polly Pocket. You know, that tiny pastel clamshell world that lived in every kid’s backpack and somehow made Barbie look like a high maintenance diva with too much luggage.

Kate’s note hit me right in the feels. Her legendary father passed away in 2024 and she shared how she’s been honoring her dad’s legacy through a mix of nostalgia, art therapy, and healing, reflecting on how toys aren’t just plastic, but emotional totems. That idea made me think how these little objects we obsessed over as kids weren’t just playthings. They carried our imagination, our escape, and sometimes even our comfort when the real world felt too big.

The truth is I never played with Polly Pocket toys. I did have a collection of Mighty Max toys, which was an outgrowth from Polly Pocket and geared for boys. However, I grew up with four sisters (yes, I wrote four) and they absolutely loved Polly Pocket!

So today’s piece isn’t just about Polly Pocket the toy line, it’s about why she mattered. To us, to design history, and to the generation that grew up believing magic could fit inside a one-inch hinge.

You can read Kate’s personal letter (The Truth is In The Detail) below this essay.

Polly Pocket dropped in 1989, and it was the toy line that proved you didn’t need lasers, kung fu grips, or holograms to rule the playground. Polly Pocket was small enough to fit in your jean pocket, yet somehow big enough to hold an entire world inside a pastel clamshell.

Polly Pocket came from the brilliant mind of British designer Chris Wiggs (and later licensed by Bluebird Toys). Polly Pocket was the perfect storm of miniature magic and childhood control. For us Gen X kids there was something deeply satisfying about a world that literally snapped shut when you were done. No batteries. No assembly. Just pure, pint-sized escapism.

These toys were micro universes. Each compact opened to reveal a tiny diorama of either a beach resort, fairytale castle, shopping mall, nursery, and many more. And the figures, those teeny, one-inch dolls, were indestructible little icons. They looked like they’d just walked out of a Lisa Frank daydream and had zero articulation, but that was the beauty of it. Imagination did the heavy lifting.

For Gen X girls, Polly Pocket was a small little world that gave them power. You could carry your own world in your pocket. Barbie needed a dream house the size of a dishwasher, but Polly had a universe that fit in your palm. That kind of portability felt futuristic, almost defiant in an age of excess.

Today, the originals are highly collectible. Mint Bluebird sets can fetch hundreds on eBay, and they’re a tangible reminder of when toy design was clever, compact, and unapologetically weird. Before smartphones shrunk our worlds, Polly did it first, and she did it with way more charm.

So here’s to Polly Pocket, the tiny plastic architect of many young girl’s daydreams, who taught us that sometimes the best worlds come in small packages… and snap shut with a satisfying click.

The Truth is in the Detail

by Kate Wiggs

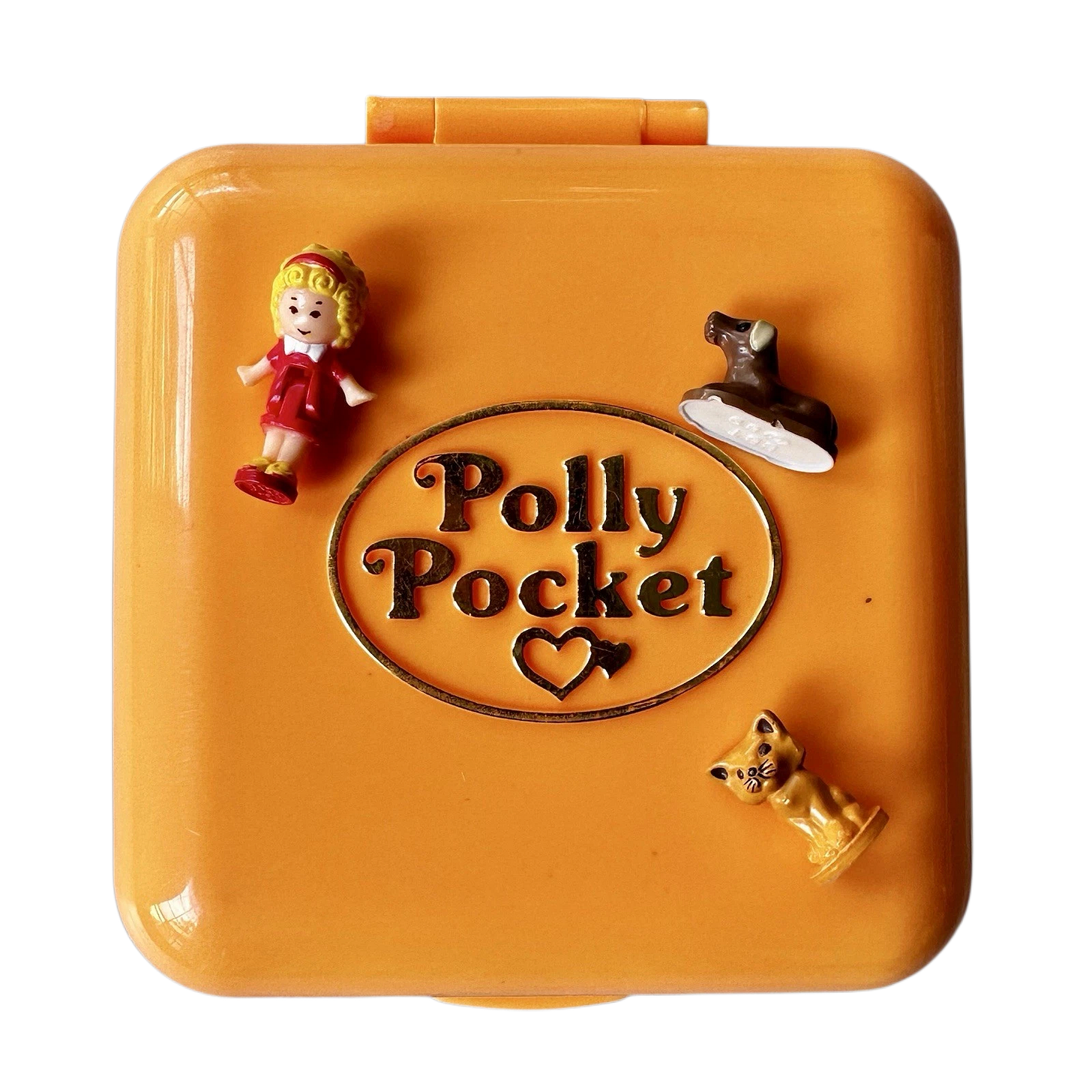

My Dad always said: ‘The truth is in the detail’—a philosophy extending from design to life itself. I remember one visit to a stately home where even the plainest wooden cabinets bloomed with gold rococo flourishes so intricate that he remarked, “even the cupids have cupids on them.” I felt in those maximalist layers a visceral urgency, a straining toward transcendence through wax-cast gold and brass that it might elevate us at a spiritual level. This obsession with precision would define everything he created, including the tiny universe he placed in my four-year-old hands.

It was September 1982 when I heard Dad say my name with that familiar question mark at the end.

“Katy?”

That hint of a question told me he wanted to show me something. This happened often with my smooth-faced thirty-three-year-old father—where I was concerned, he thought about everything before he did it. I looked directly at his hands, held at my eye level. In his palm sat a bright yellow, flattish disc with a barely visible clasp.

I kept looking.

He pressed the clasp.

The disc opened.

At four, I had a fairly good grasp of the material world. I knew that fruit was soft, that soap and water could make hand-sized bubbles with rainbow colours tumbling inside them, that sugar mice hidden on sunny windowsills developed patchy white coatings but still tasted wonderful. All in all, I knew enough to know that yellow flattish discs don’t open up to reveal entire universes containing limitless other universes inside.

Except this one did.

I didn’t say anything. Neither did he. There was nothing to say. That question mark had communicated everything: Can I show you something? Do you see? Do you understand?

I understood. An entire universe, made the correct size for my hands, and then placed into them.

For several years following that day, I always had ‘Me’s ‘ouse’ with me. It was the perfect toy, endlessly recreating itself. When I felt the need for a quiet place to withdraw to, it provided that. When I felt bright and cheery, it reflected that back. I had the experience of having my inner world mirrored over and over, until the day Dad found it at the bottom of our red wooden toy chest and understood the potential, the ‘everyman’ quality of this simple doll and her portable universe.

Dad’s early life was far from easy, and he grew protective of the quick mind and precocious creative skill that he learned to hide within the hostile environments of his childhood. This meant that rather than being quashed, they proved to be his best assets. It also meant he had an instinctive sense of what it meant to have a sanctuary of one’s own, something no adult could enter without permission, something that could travel with you wherever you went.

Shortly before he died, Dad asked me to write the story, and the graphic novel format feels like the natural approach, because so much of our early lives were visually orientated. He would always create models for us to explain new concepts, very much a believer in ‘show me don’t tell me.’ As a result, my brother and I had our visual skills developed from day one; my brother became an animator and me an artist and art therapist. I’d written around 30,000 words of the story and was feeling stuck with the traditional memoir approach when I came across the idea that graphic novels work best when there are strong visual characters. Immediately, I saw in my mind’s eye the three main characters as they would appear illustrated, and the idea has been with me ever since.

There’s something pleasing about using a visual medium to tell the story of a man who believed the truth lived in the smallest details, from the tiny but robust hinges, the dual layered mouldings inside the original compacts and the hidden battery compartments. Dad taught me that universes could fit in your palm, that love could be expressed through engineering solutions, and that sometimes the most profound truths are found not in grand gestures but in the focus inwards, looking to the quiet place where the magic happens.

Kate’s website | Kate’s Substack

Reader question: Did you have Polly Pocket toys?

Mahalo for sharing this story, and especially to your father for creating Polly Pocket

Creating a toy that has brought joy to so many children is a wonderful legacy

While I never owned any, I'm certain that Galoob was inspired by Polly Pocket when they made these mini Star Wars playsets that I enjoyed as a boy

https://www.lulu-berlu.com/upload/image/star-wars---galoob-micro-machines---chewbacca---endor-transforming-playset-p-image-512962-grande.jpg

I love this! I was a huge fan of these growing up. I've noticed that Polly Pocket is still around, why did the actual size of her get bigger?